BLOG

ACL Injuries Part 3: What ACL Rehab Should Look Like

Here we are. We can finally talk about what your ACL rehab should really look like. The previous blogs we covered the trends of ACL injuries and how it affects young athletes the most as well as the number one thing you or your athletes will want to do when an ACL injury occurs.

Nov. 9, 2023

Dr. Donald Mull, DC

Here we are. We can finally talk about what your ACL rehab should really look like. The previous blogs we covered the trends of ACL injuries and how it affects young athletes the most as well as the number one thing you or your athletes will want to do when an ACL injury occurs.

Now we can talk in greater detail about what an athlete’s rehab should look like if the goal is to get back to playing sports and decrease the risk of re-injury as much as we can.

1 in 5 athletes sustain reinjury upon returning to high-risk sports after ACL reconstruction(1) and only 28% of NFL players are active in the league 3 years after an ACL injury and subsequent reconstruction.(2) I personally think we can do a better job with these rates, at least in regards to the rehab process.

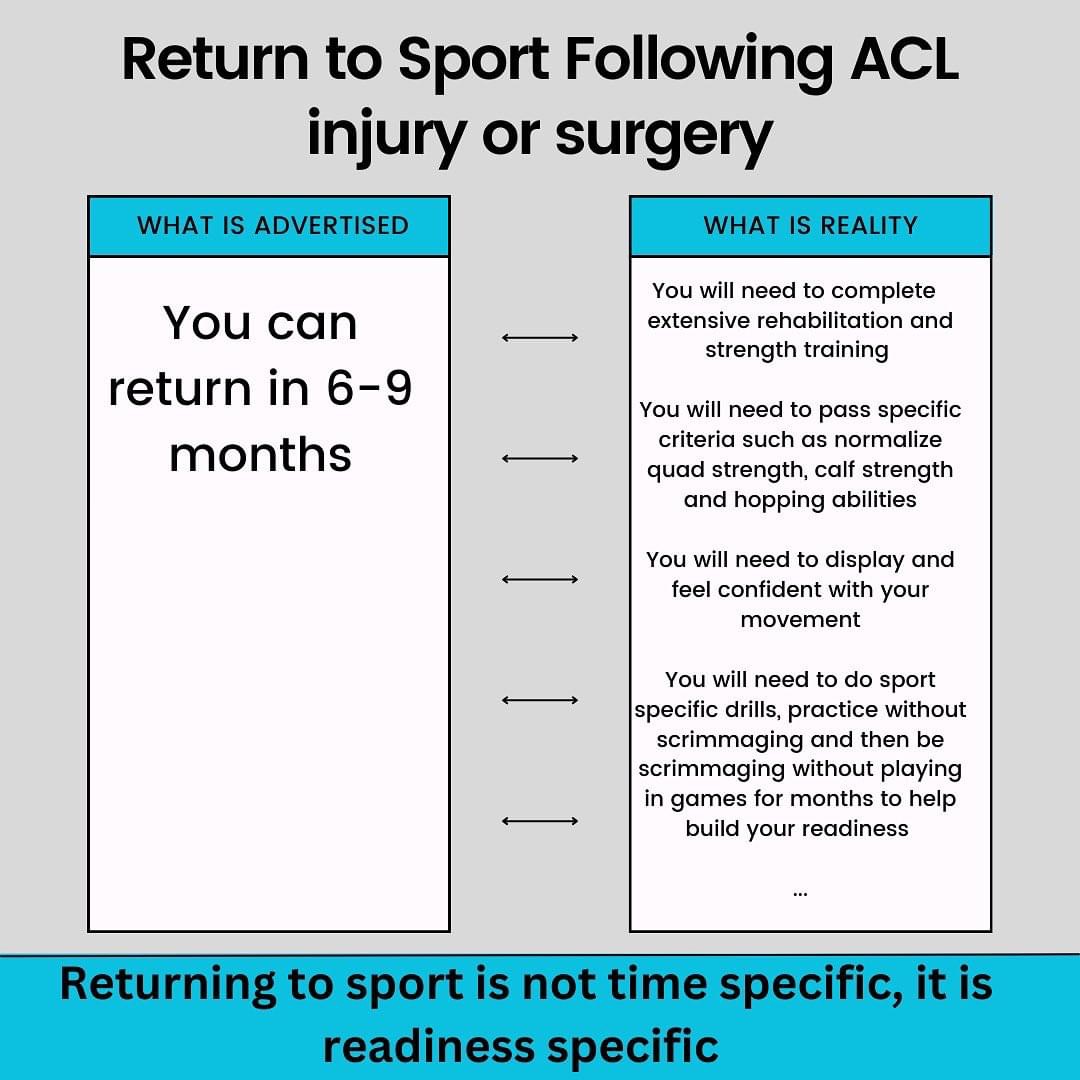

The story most parents and athletes get told is “It will take 6-9 months after surgery to return back to their sport.” By the end of this blog, my hope is you know why this is not only incomplete thinking but also one that puts athletes at risk.

There is no perfect protocol that works best for every athlete, but I do think we have enough evidence for guidelines and principles that an athlete should follow if we want to minimize the risk for re-injury. (3) The sad truth is, most athletes are NOT doing these things.

Below are the areas that I think are non-negotiable in terms of what should be included in ACL rehab:

- Early Testing for TRUE baseline

- Broad testing with BOTH qualitative and quantitative feedback

- BOTH timeline and functional outcome guidelines

- Deep understanding of the demands of the sport

- Strength & Conditioning Training early and often

- Stepwise return to sport or activity

I think each of these points are worth elaborating on, so here we go.

Early Testing for ACL Injuries

We did talk about this in the last part of this blog, so this should serve more as a recap than anything. The current “standard” for most rehab protocols uses the comparison of the strength or power on the non-surgical leg (called limb symmetry index) to guide rehab progressions and return to play. Though this is one thing to monitor in regards to progress, this is not sufficient evidence that the athlete is back to pre-injury status. Here is why…

Limb symmetry index is not a true indicator if an athlete is as strong or powerful as they were pre-injury. The only way to know this is to have an objective measure prior to the injury or at least of the non-injured leg ASAP prior to any fall off in strength or power. This means within days or 2 weeks max from their injury. Even if it has been longer than this, the sooner the better.

If a true baseline measurement wasn’t taken all you have to compare the surgical leg to is the non-surgical one which is also weak. Even if there is 90 plus percent equality side to side, aren’t we still drastically short of the mark? Are we returning our athletes weaker than they have ever been and wondering why reinjury rates are so bad?

We know that those who get back to pre-surgical strength are much less likely to experience a reinjury after returning to sport when compared to using limb symmetry index (comparing the non-injured during late stage rehab).(4)

The problem is that no one is doing this! No one is prioritizing getting a true baseline measurement of strength and power as soon as they can after an ACL injury before that non-surgical leg becomes weak as a result of decreased activity.

This is why for anyone who has been diagnosed with an ACL injury, we are offering a baseline assessment FREE of charge. This is how much we think this NEEDS to be a major priority for athletes who have suffered from an ACL injury.

What should be tested for ACL injuries

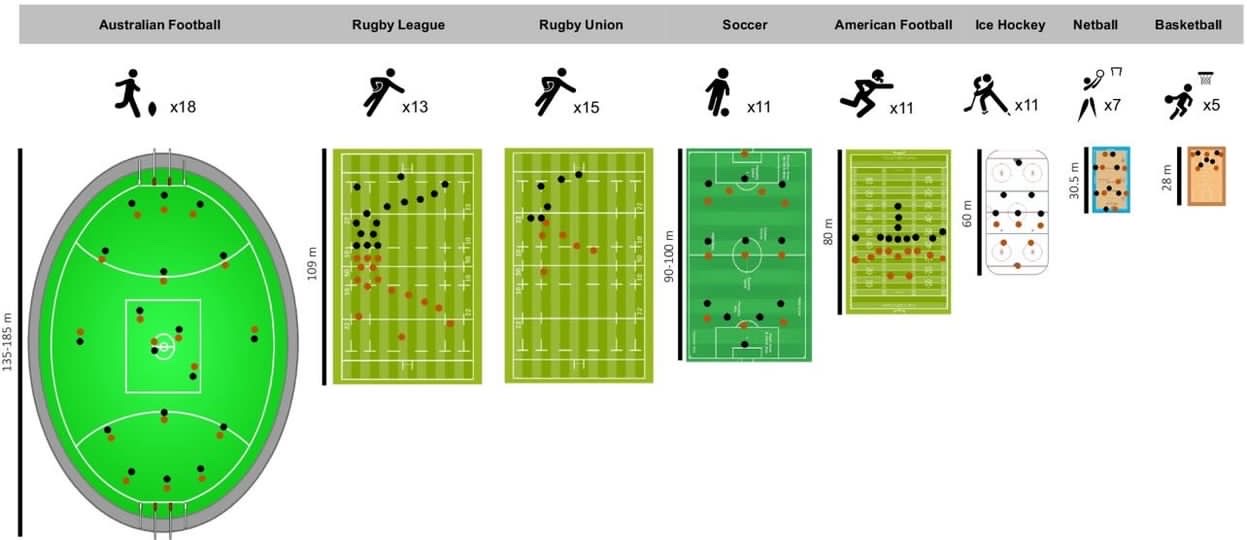

There is no consensus on what should be tested for every athlete to put them in the best position to avoid reinjury. This makes sense to me. Not all sports are the same nor are all athletes the same.

The criteria of what tests should be used for return to sport should be curtailed to the athlete based on the demands of the sport as well as the abilities and goals of the individual athlete.

In general though, we know that athletes need to be both strong in isolated movements as well as integrated ones. We have seen this in studies that have combined both strength and hop testing in the return to play criteria, which show those who do well in both are more likely to be healthy in a one year follow up after returning to sport compared to those who only do well in one or the other (5).

This should be no surprise. Athletes are some of the best at figuring out ways to achieve a given task - this is often what makes them good athletes. We see this when you ask an athlete to perform common jump tests in ACL protocols. They will figure out a way to accomplish it, using any muscle or strategy they can and are able to hide massive imbalances that can only be seen in tests that isolate single movements or muscle groups, even as late as 1 year post surgery! (6)

The problem isn’t that jump tests are not valuable to measure and compare to a baseline. The problem is that it is not enough information to make conclusions about where that athlete is in regards to the recovery process. We need more information.

For example, traditional hop tests in the clinic measure how far an athlete can jump because it is very cheap and accessible. You just need clear instructions and a tape measure. However we have seen that athletes can do extremely well in these horizontal jumps, yet still have significant weakness and deficit when it comes to jumping vertically (7). Every sport requires forces to be expressed not only horizontally but also vertically and every combination in every way.

This is why I think it is important to cast a wide net when rehabbing an athlete recovering from an ACL injury. The more detailed the profile the more we can understand where that athlete is in the process and how well or poorly they are responding to the training stimuli.

We can stack up the objective evidence in terms of strength, power etc until we are blue in the face but oftentimes the athlete themself knows best. When an athlete does not feel confident in their body or feel like they can return, they are up to 13x more likely to re-injure their ACL within 2 years of returning to sport! (8,9) We need to make sure we are implementing some sort of questionnaire where the athlete can freely provide feedback on how confident they actually feel about returning to activity.

Like mentioned before there is no consensus to which tests should be used to ensure the best odds possible to avoid reinjury. However, the following is what we prefer and feel are extremely reasonable in general contexts:

- Pre injury or early baseline strength & power testing (Covered in detail here)

- Isolated Strength (Quad, Hamstring, Calf)

- Jump Tests (Vertical, Horizontal & Lateral)

- Change of direction test (5-10-5, etc)

- Qualitative drills (sport specific and body control feedback)

- Confidence questionnaire

This allows the freedom to curtail the specific objective measures to the individual athlete and covers enough bases to ensure the athlete is as close to pre-surgery as possible. ACL injuries take a long time and the road to recovery is not easy. We need to make sure we are putting our youth athletes in the best possible position to avoid this painful journey for a second time. We NEED to be better. Athletes should be prepared for at least 9 months of vigorous and intensive rehabilitation.

How long will ACL rehab take?

The road to recovery for ACL injuries is a long and arduous process. I think it is important to lay out the expectations as clearly as possible from day one. There will be a lot of hard work and training necessary and patience is absolutely required so be prepared to be in it for at least 9 months.

You know the saying “time heals all wounds”? Yeah, that is not quite enough in regards to returning from an ACL injury and the subsequent reconstruction. Time alone will not put an athlete in the best possible scenario to avoid future injuries.

I don’t think we can really answer how long ACL rehab will take without taking into consideration the entire picture. The answer lies in marrying timelines, functional outcomes and the confidence of the individual athlete.

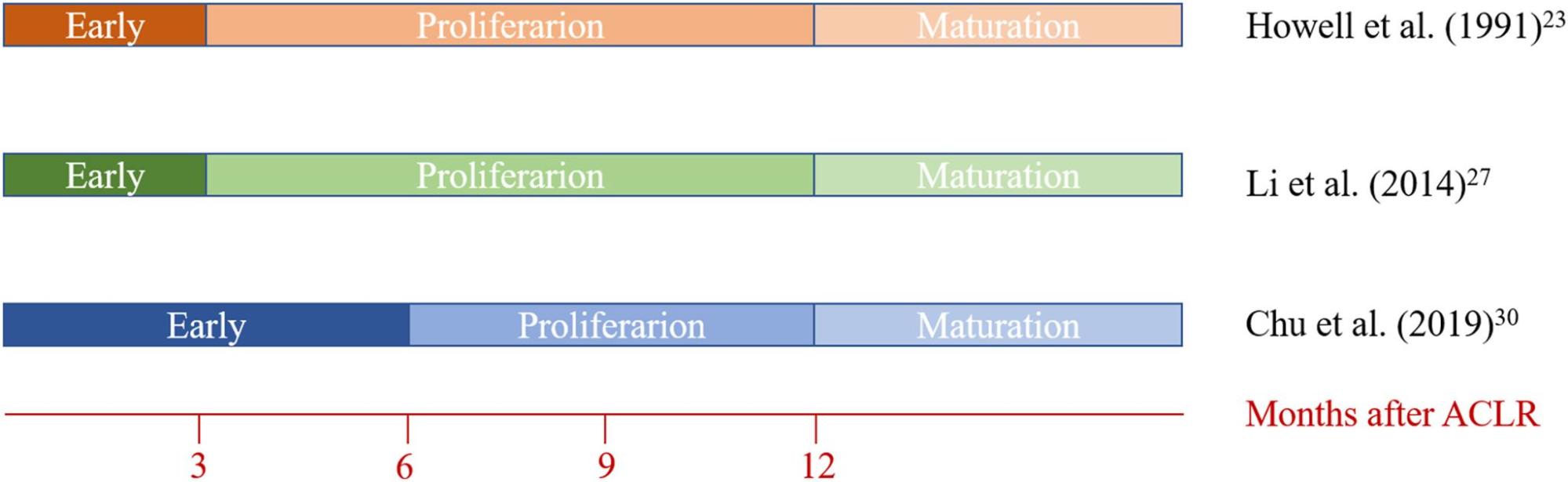

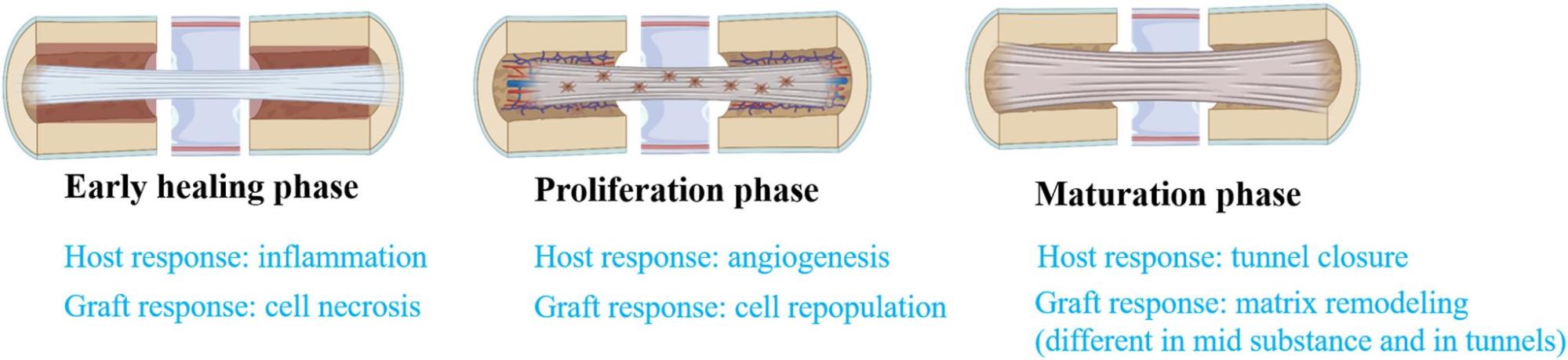

First it takes time for the graft that is drilled into the thigh and leg bone to heal enough to be structurally sound. The graft undergoes three stages of healing (early, proliferation and maturation) and doesn’t seem to enter into the third stage until 12 months after surgery. (10)

This is important, considering a large number of athletes return to play prior to one full year post surgery. We also have evidence that the reinjury rate is reduced by 51% for every month an athlete waits to return to play between months 5 and 9 post surgery. (11) After 9 months this study saw a drastic fall off in difference in regards to reinjury rates.

This has pushed some professionals to make a clear delineation that an athlete should not go back to their sport until after 9 months. Though I think this is well meaning and don’t disagree, I do think it is a misrepresentation of the literature.

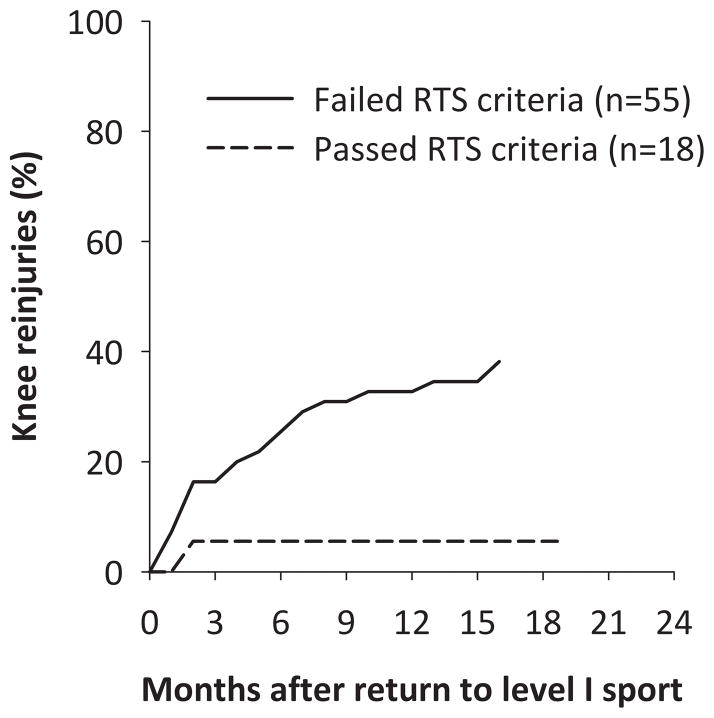

The above mentioned study also shows that only 24% of the athletes met the criteria to pass the functional testing that included strength, hop testing (power) and self reported outcomes (confidence).

So I do agree in a general context that an athlete should prepare for at least 9 months of vigorous and intensive rehab for 9 months to allow the graft to get as close to maturation as possible.

During this timeline where the graft is healing, an athlete needs to be preparing their body for the demands of their sport. This is done by getting as strong and as powerful as humanly possible, ideally exceeding their capacities prior to their surgery.

We know that those who do not pass a cluster of return to sport (RTS) criteria that includes strength, power and confidence outcomes are at higher risk for reinjury after returning to sport.(12)

In order for an athlete to get to where he or she was prior to the surgery, this will take work. Work in the form of strength training, mobility training, jump training, sprint training, metabolic conditioning.

The rehab should look a lot like strength and conditioning and the longer an athlete waits the longer it will take he or she to get back to pre-surgical levels. This work should be guided by a professional who understands how to train for the demands of the sport and can give feedback on the quality of the training.

In summary, here are things that need to be considered when making a decision to return to play after an ACL injury:

- Time it takes for graft to heal

- Time the athlete has been deconditioned

- Time to recondition the athlete

- Restoration of baseline strength and power

- Movement quality of the athlete

- Confidence level of the athlete

How long should ACL rehab take is not a straightforward answer if you are looking at all aspects and are taking into account each variable. In my opinion there is not a black and white answer, but one should expect at least 9 months to get as close to graft maturation as possible as well as give the athlete an opportunity to become as confident, as strong and as powerful as humanly possible while having the capability to pass all of the functional assessments.

So I want you to ask yourself, is the progress of your child or athlete being properly measured and managed? Does their rehab look like strength training? Are they preparing their body to meet the demands of their sport?

ACL Rehab Should Prepare an Athlete for Their Sport

If you are an athlete or just want to feel confident in moving your body like an athlete again at any level, your rehab needs to challenge you. It should not look like the same thing everybody gets when they walk into the door, nor a fixed sheet of paper of exercises.

The rehab should be catered toward your sport or push to develop the physical qualities that are necessary to be successful on the field or court. The good thing is, there is a lot of carry over from sport to sport and 80 percent of training should look similar for most popular field and court sports.

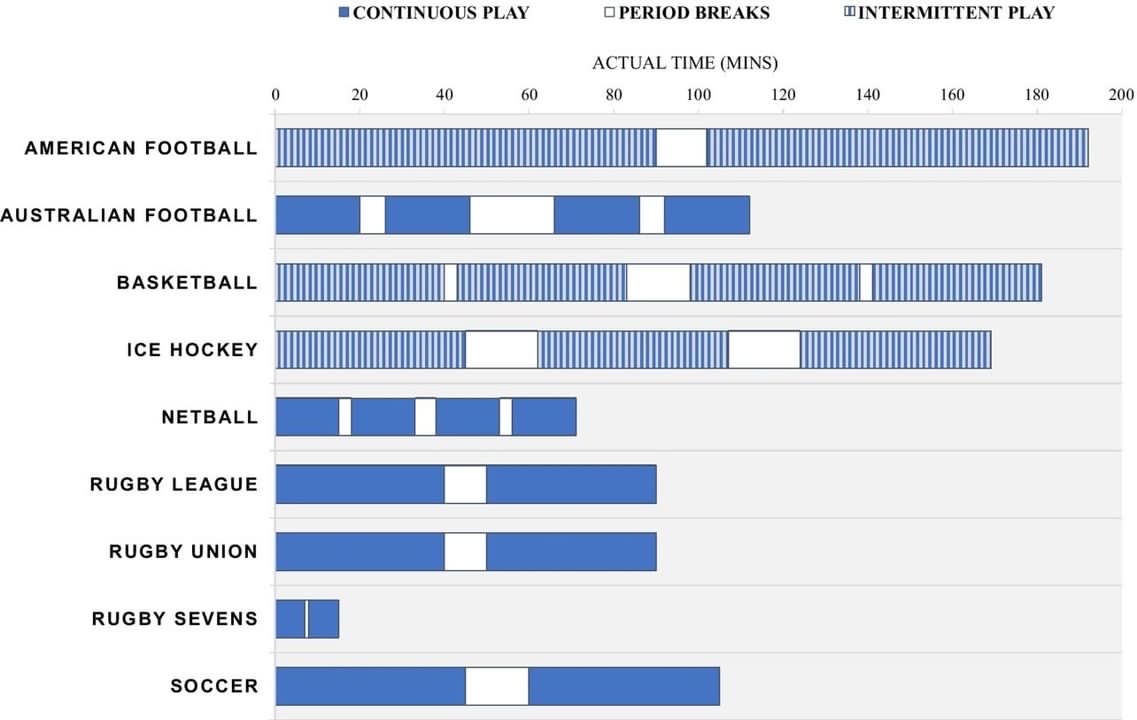

One of these differences lie in how long plays last and how long breaks last in regards to a conditioning standpoint as well as how big the court or field is from a force production and speed standpoint. (12)

The main point here is that most sports need to be able to repeat brief bouts of very intense efforts throughout the match. This requires them to be able to produce and absorb a tremendous amount of force and also be able to do so in a little amount of time.

In order for an athlete to produce force and cover ground they must develop strength, power and speed while also having the mobility to get into a wide variety of body positions. Generic band exercises, ice and stationary bikes are not going to cut it.

Athletes need to be exposed to versions of resistance training and speed training early and often. This is where having a deep understanding of the demands of their respective sport as well as extensive strength and conditioning is a must for the rehab practitioner that is working with your athlete.

The athlete should do strength training as early as possible even if it does not involve the injured leg. We know that exposing the non injured leg to high intensity or heavy resistance training decreases the amount of weakness seen in the injured leg during the time directly after the surgery (13).

Returning to Sport after ACL injuries

When returning to any level of sport, there should be a plan to return to participation in a progressive manner that gives the athlete time to feel confident and physically adapt to the stress. I do not think it is wise to push an athlete into the deep end without a clear plan and relentless support.

The athlete should be gradually exposed to certain skills or short sided activities that allow the athlete to start gaining confidence in their body again. Sports require the athlete to navigate complete chaos, blending prediction with reaction nonstop until a winner is decided. Even if the athlete second guesses themself for a fraction of a second, they are not only at a disadvantage from a competitive standpoint, we can assume the risk for injury also increases. We need to remember that this injury affects both mind and body.

Slowly exposing the athlete to their sport in a progressive manner gives them adequate time to feel their body move like an athlete again and the body itself the time to adjust to the physical stress. The last thing we want to do is spike the athlete’s activity too fast too soon and drive a set-back or worse retear the ACL. We know from sport science research that there is a sweet spot of exposure where if the athlete is exposed to a drastic increase in workload the risk of injury also increases. (14)

This is why it is important for the rehab professional to expose the athlete to versions of running, jumping and/or cutting early and often in the rehab process. It can then be scaled up slowly and progressively over time, avoiding spikes in demand during the process. This is why I am bullish on making sure strength training is present and is challenging, fun and encouraging for the athlete.

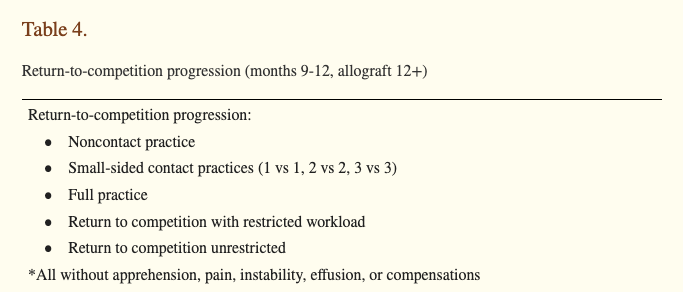

In my opinion, this makes the return to sport or practice process much less intimidating because the athlete has been exposed to elements of the game and feels prepared both mentally and physically. When they are ready to return to some level of sport, it is in their best interest to do so in a stepwise fashion. A reasonable example shown below is the resumption of non contact practice, followed by small-sided contact practices (1 vs 1, 2 vs 2, 3 vs 3 drills, etc), full unrestricted practice, return to competition at restricted workload, and last, return to competition unrestricted. (3)

Though there is no perfect “protocol” that fits every athlete’s situation, I do think we have so much room to get better in this space. If we want the re-injury rates to improve, physical therapy and rehab will need to consider far more than the current standards.

It is not enough to be given a timeline, an athlete needs to be aiming for specific targets that can be measured and tracked. The clinician and/or coach should be there to provide guidance and feedback on how to get there as soon as possible.

No one likes to be sidelined for any given amount of time. To get the most out of rehab work with a team who knows what you need to be training for.

My friend and phenomenal PT from Albany, NY put it best “Return to sport is not timeline specific, it is readiness specific”. Surround yourself or your athlete with a team that understands this and knows how to train your athlete for the game.

References:

- Barber-Westin S, Noyes FR. One in 5 Athletes Sustain Reinjury Upon Return to High-Risk Sports After ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review in 1239 Athletes Younger Than 20 Years. Sports Health. 2020 Nov/Dec;12(6):587-597. doi: 10.1177/1941738120912846. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32374646; PMCID: PMC7785893.

- Mody KS, Fletcher AN, Akoh CC, Parekh SG. Return to Play and Performance After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in National Football League Players. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022 Mar 7;10(3):23259671221079637. doi: 10.1177/23259671221079637. PMID: 35284583; PMCID: PMC8905068.

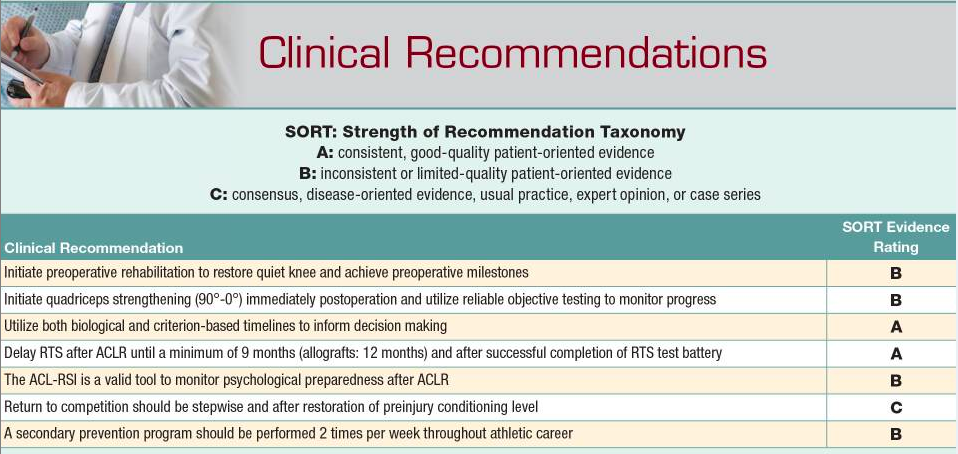

- Brinlee AW, Dickenson SB, Hunter-Giordano A, Snyder-Mackler L. ACL Reconstruction Rehabilitation: Clinical Data, Biologic Healing, and Criterion-Based Milestones to Inform a Return-to-Sport Guideline. Sports Health. 2022 Sep-Oct;14(5):770-779. doi: 10.1177/19417381211056873. Epub 2021 Dec 13. PMID: 34903114; PMCID: PMC9460090.

- Wellsandt E, Failla MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Limb Symmetry Indexes Can Overestimate Knee Function After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 May;47(5):334-338. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7285. Epub 2017 Mar 29. PMID: 28355978; PMCID: PMC5483854.

- Toole AR, Ithurburn MP, Rauh MJ, Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Schmitt LC. Young Athletes Cleared for Sports Participation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: How Many Actually Meet Recommended Return-to-Sport Criterion Cutoffs? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Nov;47(11):825-833. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7227. Epub 2017 Oct 7. PMID: 28990491.

- Barfod KW, Feller JA, Hartwig T, Devitt BM, Webster KE. Knee extensor strength and hop test performance following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee. 2019 Jan;26(1):149-154. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2018.11.004. Epub 2018 Dec 13. PMID: 30554909.

- Zarro MJ, Stitzlein MG, Lee JS, Rowland RW, Gray VL, Taylor JB, Meredith SJ, Packer JD, Nelson CM. Single-Leg Vertical Hop Test Detects Greater Limb Asymmetries Than Horizontal Hop Tests After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in NCAA Division 1 Collegiate Athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021 Dec 2;16(6):1405-1414. doi: 10.26603/001c.29595. PMID: 34909247; PMCID: PMC8637251.

- McPherson AL, Feller JA, Hewett TE, Webster KE. Psychological Readiness to Return to Sport Is Associated With Second Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2019 Mar;47(4):857-862. doi: 10.1177/0363546518825258. Epub 2019 Feb 12. PMID: 30753794.

- Paterno MV, Flynn K, Thomas S, Schmitt LC. Self-Reported Fear Predicts Functional Performance and Second ACL Injury After ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport: A Pilot Study. Sports Health. 2018 May/Jun;10(3):228-233. doi: 10.1177/1941738117745806. Epub 2017 Dec 22. PMID: 29272209; PMCID: PMC5958451.

- Yao, S., Fu, B. S.-C., & Yung, P. S.-H. (2021). Graft healing after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR). Asia-Pacific Journal of Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation and Technology, 25, 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asmart.2021.03.003

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(13):804-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031. Epub 2016 May 9. PMID: 27162233; PMCID: PMC4912389.

- Torres-Ronda L, Beanland E, Whitehead S, Sweeting A, Clubb J. Tracking Systems in Team Sports: A Narrative Review of Applications of the Data and Sport Specific Analysis. Sports Med Open. 2022 Jan 25;8(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s40798-022-00408-z. PMID: 35076796; PMCID: PMC8789973.

- Minshull C, Gallacher P, Roberts S, Barnett A, Kuiper JH, Bailey A. Contralateral strength training attenuates muscle performance loss following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: a randomised-controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2021 Dec;121(12):3551-3559. doi: 10.1007/s00421-021-04812-3. Epub 2021 Sep 20. PMID: 34542671.

- Maupin D, Schram B, Canetti E, Orr R. The Relationship Between Acute: Chronic Workload Ratios and Injury Risk in Sports: A Systematic Review. Open Access J Sports Med. 2020 Feb 24;11:51-75. doi: 10.2147/OAJSM.S231405. PMID: 32158285; PMCID: PMC7047972.

Related Posts

Why does my shoulder keep hurting?

You are not alone: Shoulder injuries are one of the most common injuries, especially those who are active, are overhead athl...

Read more

To Sit or to Stand? That is the Question.

I frequently get asked about sit to stand desks and what benefits they may or may not have. The numbers for people with chron...

Read more

What to Expect from a Visit to Kinetic Impact

What You Can Expect... At Kinetic Impact our focus is on keeping our clients active and pain free. Our holistic approach comb...

Read more

Search the Blog