BLOG

ACL Injuries Part 2: Priority #1 on Day 1

In the first part of this blog on ACL injuries, we talked about how ACL injuries have been on the rise and the unfortunate truth is that our youth athletes are the ones affected most. We also unveiled how reinjury is all too common, one in five athletes experiencing a reinjury upon returning to high-risk sports after an ACL reconstruction.

Oct. 30, 2023

Dr. Donald Mull, DC

In the first part of this blog on ACL injuries, we talked about how ACL injuries have been on the rise and the unfortunate truth is that our youth athletes are the ones affected most. We also unveiled how reinjury is all too common, one in five athletes experiencing a reinjury upon returning to high-risk sports after an ACL reconstruction.(1)

This article is for someone who recently has an ACL injury or someone they know has recently experienced an ACL injury or if you have an athlete who participates regularly in a field or court sport. Even if this athlete has yet to have surgery, now is the time to set them up to have the best odds for a successful return to sport.

In my opinion, prior to surgery or as soon as possible a good place to start is to get an athlete’s baseline level of strength and power on the non-involved leg. This is the only way to get a TRUE baseline measurement for an athlete to aim for during the rehab process. An athlete who is given functional measures to train for is much more likely to succeed than one who is just given a timeline of 6-9 months to return. There is no direction in a timeline and the athlete needs to know where to go and how to get there.

Doing this as soon as possible ensures that the athlete’s strength and/or power has not diminished due to lack of sport participation. Typically the athlete goes for weeks if not months prior to testing this and in some cases never at all. So imagine you or your athlete tears their ACL, it typically takes 1-3 weeks to diagnose via MRI and an additional 2-3 weeks (if you’re lucky) to have the procedure. PT then usually starts 1-2 weeks after the surgery.

We are now at 8 weeks and if the PT clinic has the knowledge to measure the strength and/power of the non-injured leg to get a baseline, but by this point there has been a drastic decrease in strength and power given the athlete has been sidelined awaiting diagnosis, surgery and post surgical care. This baseline is grossly skewed to be much weaker and slower - this is NOT the true baseline.

Now let’s fast forward 5-6 months as rehab has progressed. Most PT clinics, again if they even measure outcomes, use something called limb symmetry index to create their return to play criteria. Essentially they compare the strength, coordination and/or power to the non surgical leg and then decide how to progress rehab and/or decide what the athlete is cleared to do.

For example, if an athlete’s quad and hamstring on the surgically repaired leg is 80 percent as strong as the non-surgical leg or can jump 80 percent as far as the non-surgical leg most PT clinics will clear the athlete to run and progress rehab to be more “intense”. Theoretically this makes logical sense. However, the logic is flawed because the non-surgical leg is also weak relative to their initial abilities.

Remember it has been MONTHS of deconditioning before the non surgical leg has been measured.

This may not be an issue for the athlete in the gym or in a PT clinic when performing predictable movements in a controlled setting. However, even if the athlete gets to 100 percent compared to the non-surgical leg; are they really as good as they were pre-injury? How will you ever know?

You can’t expect an athlete who is deconditioned, weaker and slower not to have an increased risk of injury. This is in fact the perfect recipe for injury. No wonder why the reinjury rate is so high.

You NEED to prioritize getting a baseline to know if the athlete is physically as capable as they were pre-injury.

In my opinion you should test three things on the non-injured leg ASAP after injuring an ACL (or if you really want to be preventative you can do this on both to have a working baseline, which would be fabulous and typically only reserved for professional athletes):

- Quadriceps strength

- Hamstring strength

- Single leg vertical jump height

To be clear, the reason I have such a strong opinion is because I have heard some horror stories about the care that athletes have received. I think PT manages athletes away from load for FAR too long which creates a massive gap in physical capabilities and conditioning. PT should look very similar to strength and conditioning as soon as possible or at least involve a strength coach as soon as possible. However I will save this topic for another day, maybe I will call it “Part 3: What ACL Rehab Should Look Like”.

Secondly, when following the research the numbers do not lie. Using an athlete's strength pre-surgically instead of using limb symmetry 6 months post operation is a better predictor for future injury of an athlete(2). Meaning those who do reach pre-surgical strength and power are much less likely to experience a re-injury.

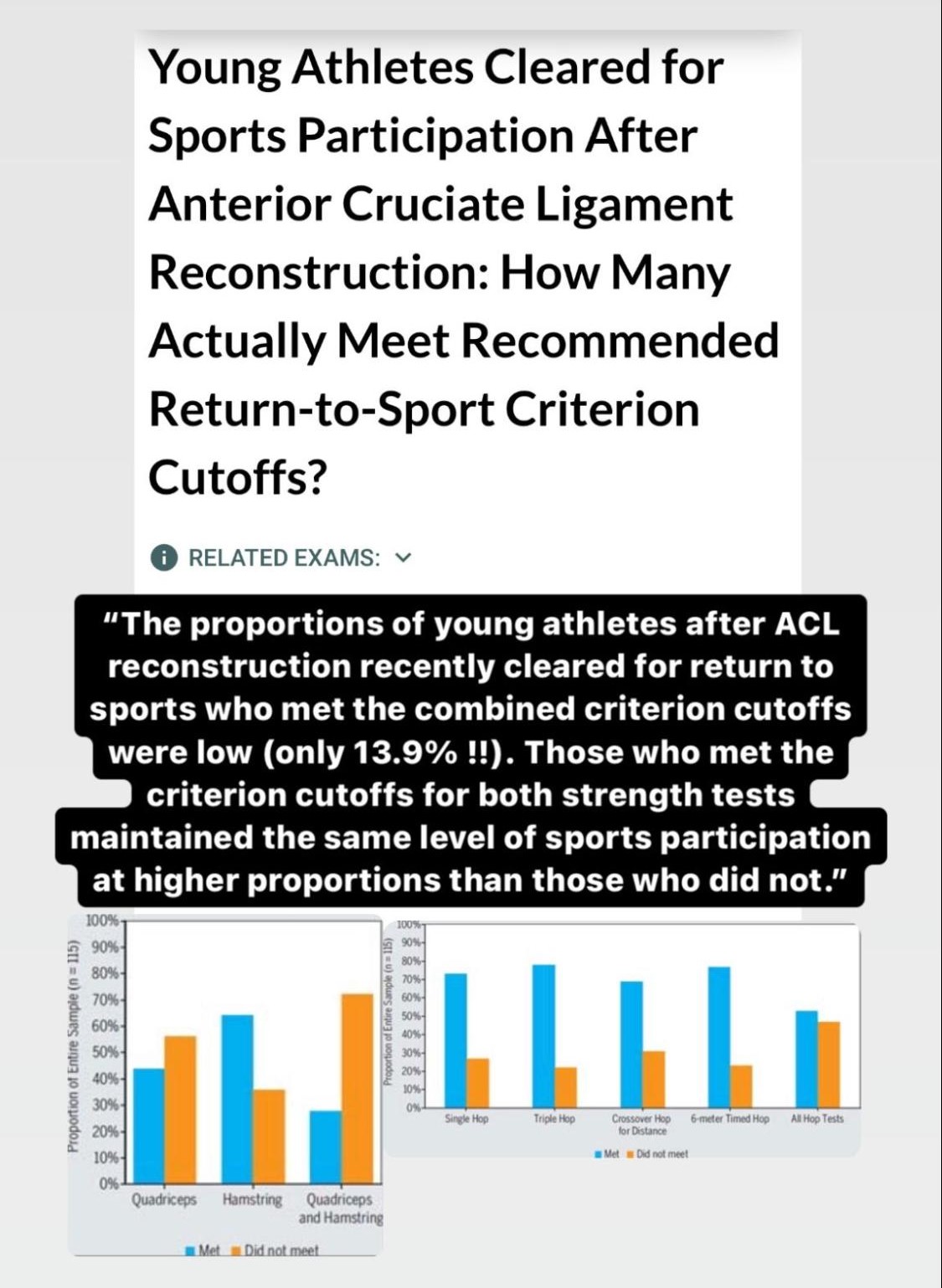

In addition, if you combine both strength and hop testing in the return to play criteria an athlete has been shown to be more likely to be healthy in a one year follow up after returning to sport (3). This should be the goal at the end of the day right?

How often we hear an athlete not meeting these minimum requirements is concerning to us. I am not naive enough to think we can prevent all re-injuries, however I do think we can drastically stack the odds in the favor of the athlete if we do the following during the rehab process:

- Get baseline strength/power measurement when healthy or ASAP post ACL injury

- Restore ROM early

- Continue whole body strength training early and often

- Maintain a base of aerobic conditioning and conditioning specific to sport

- Expose plyometrics, sprinting, cutting and reactive training weeks to months prior to returning

- Restore strength and power to baseline prior to return to sport

We are extremely passionate about this topic because quite frankly, I feel there is such an incredible opportunity to have a positive impact on the athletes that have become apart of the rising statistics of an ACL tear. This is why we offer free testing for those waiting or who just had an ACL reconstruction (remember the earlier the better). Click here if you’d like to learn more.

In the meantime, I’ll get to work on Part 3: What ACL Rehab Should Look Like.

Resources

- Barber-Westin S, Noyes FR. One in 5 Athletes Sustain Reinjury Upon Return to High-Risk Sports After ACL Reconstruction: A Systematic Review in 1239 Athletes Younger Than 20 Years. Sports Health. 2020 Nov/Dec;12(6):587-597. doi: 10.1177/1941738120912846. Epub 2020 May 6. PMID: 32374646; PMCID: PMC7785893.

- Wellsandt E, Failla MJ, Snyder-Mackler L. Limb Symmetry Indexes Can Overestimate Knee Function After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 May;47(5):334-338. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7285. Epub 2017 Mar 29. PMID: 28355978; PMCID: PMC5483854.

- Toole AR, Ithurburn MP, Rauh MJ, Hewett TE, Paterno MV, Schmitt LC. Young Athletes Cleared for Sports Participation After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: How Many Actually Meet Recommended Return-to-Sport Criterion Cutoffs? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2017 Nov;47(11):825-833. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2017.7227. Epub 2017 Oct 7. PMID: 28990491.

Related Posts

4 Ways to Quickly Relieve Tight Muscles (including detailed video examples)

In a previous blog Why Do Muscles Feel Tight, we talked about why your muscles get tight. Now we have a sense of what may be ...

Read more

“Are Dancers Athletes?”

The simple answer to this question is F#$k yes they are! And for any dance athletes reading this you need to see yourself thi...

Read more

Can I Exercise with Low Back Pain?

If I was forced to answer this simply, a Stone Cold Steve Austin “Can I get a Hell Yeah?” would swiftly follow. Since we are ...

Read more

Search the Blog